Bardzo mi przykro, ale lekcje na platformie The Blue Tree działają jedynie na komputerze lub tablecie.

Do zobaczenia na większym ekranie 🙂

Zespół The Blue Tree

warm up

Answer the questions below. Listen to the model answers and report back on what you’ve heard.

| What is your favourite season of the year, and why do you like it so much? |

TRANSCRIPT

My favourite season is spring. I love that everything slowly comes back to life after winter. The days get longer, the air feels fresher, and people seem to be in a better mood. I also like that it’s not too hot or too cold, so you can be outside more. For me, spring feels like a fresh start and a good moment to make new plans.

| People live even in the coldest places on Earth, such as Yakutsk. Why do you think people choose to live in such harsh conditions? |

TRANSCRIPT

I think people stay in very cold places for different reasons. Some were born there and feel emotionally connected to their home, family, and culture. Others might work in industries like mining or science, so they don’t really have a choice. Also, when you grow up in a harsh climate, it becomes normal. What seems extreme to outsiders can feel familiar and manageable to locals.

| Climate change is causing more extreme and unpredictable weather. How prepared do you think you and your family are for such events? |

TRANSCRIPT

To be honest, I don’t think my family is very well prepared. We rely a lot on electricity, heating, and shops being open all the time. We don’t have big food reserves or a clear plan for emergencies. I think we assume serious problems won’t happen to us. Reading stories like this makes me realize that being prepared isn’t paranoia — it’s common sense.

part one

READING

You are going to read a story of the 1978 winter in Poland.

Go through the flashcards before you continue.

Listen to and read the first part of the article.

Listen to the first part. Follow the text below.

As Poland braces for another spell of extreme temperatures, older generations are once again recalling the so-called “winter of the century”—a brutal cold snap that began at the tail end of 1978 and gripped the country for weeks.

True, from a strictly meteorological perspective, Poland has weathered far harsher winters, yet it is this one that has become the benchmark on which all are now measured—not just because of its severity, but for the ripple effects it unleashed, a perfect storm of conditions that would even carry grave political consequences for the country’s leadership at the time. No one who lived through it would ever forget it.

PART TWO

Here’s the second part of the article.

Listen to the second part. Follow the text below.

It began innocuously. Christmas had passed and as rain drizzled down, many thought spring was already on its way. This, however, was wishful thinking.

If the weather over the previous days had been mild, by December 30 puddles had begun to freeze over as a high-pressure system approached from Scandinavia. By noon, temperatures in some areas had fallen to –10°C, and on the coast, high winds began to buffet Poland’s ports. Soon enough, snow started tumbling down in huge volumes.

Even so, none of this seemed too unusual, and only on New Year’s Eve did things begin to truly go awry.

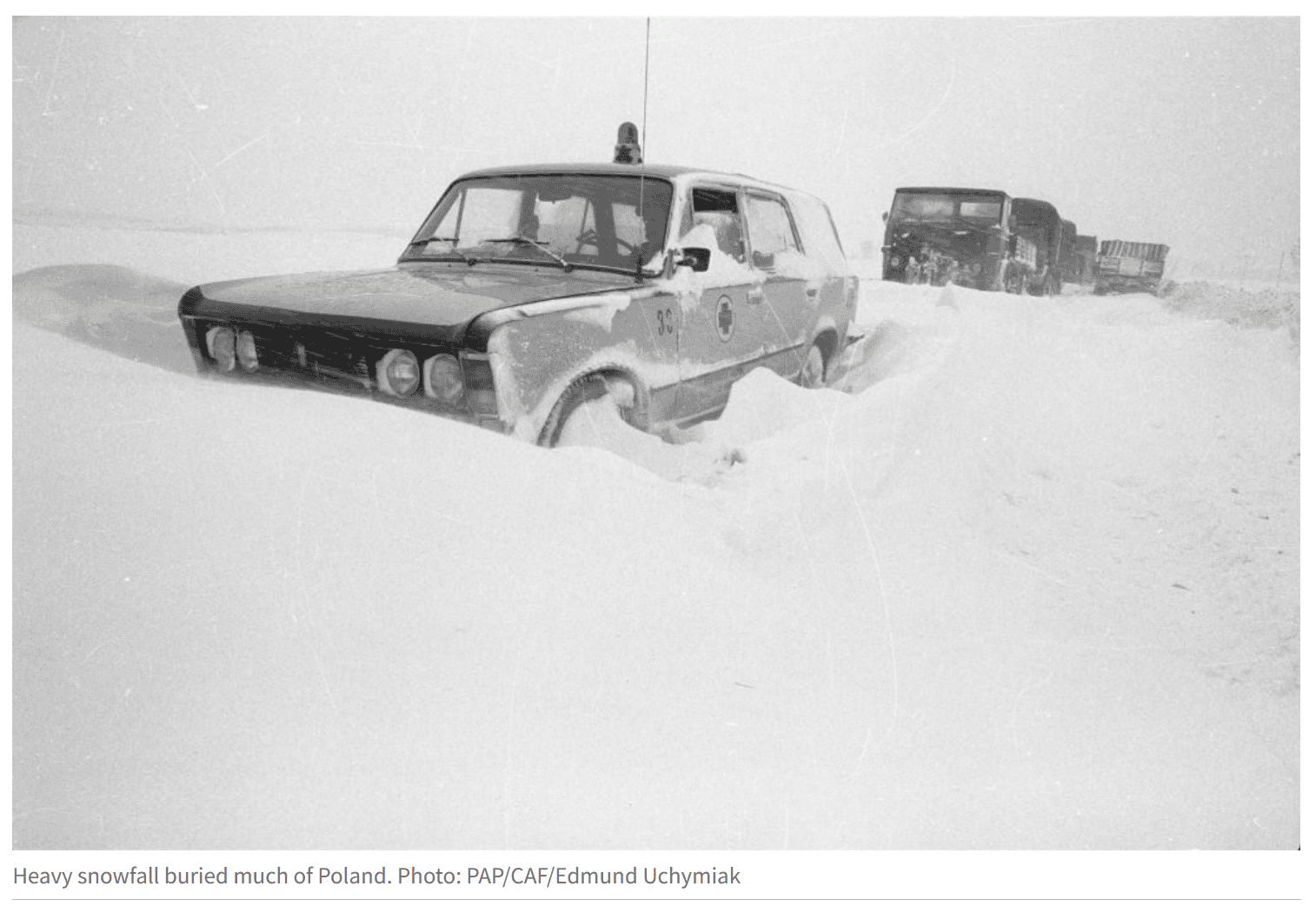

By then, thermometers had dipped to –25°C and an estimated 18,000 kilometers of roads lay buried. In some parts of Poland, snowdrifts reached heights of up to 3.5 meters.

“The orchestra for our New Year’s Eve party didn’t arrive until 1 a.m.,” Elżbieta Kryńska, a resident of Tomaszów Mazowiecki, told Newsweek Polska. “But we were lucky, because in many places neither the orchestras nor the guests ever arrived.”

Having dressed up in their ballroom finery to see in the New Year, many later spoke of ringing in 1979 alongside strangers after being left stranded, turning train station waiting rooms into impromptu parties.

PART THREE

Read the third part of the article.

Listen to the third part. Follow the text below.

Amusing as this sight may have been, it soon became clear that what was unfolding was no laughing matter: in Lublin, for instance, partygoers were said to have come close to death as they battled to get home in skimpy evening wear. Some, it was claimed, took two days to return.

The high-pressure system sweeping in from the north had collided with a low-pressure system pushing up from southern Poland, whipping up huge winds that served to only intensify the chill.

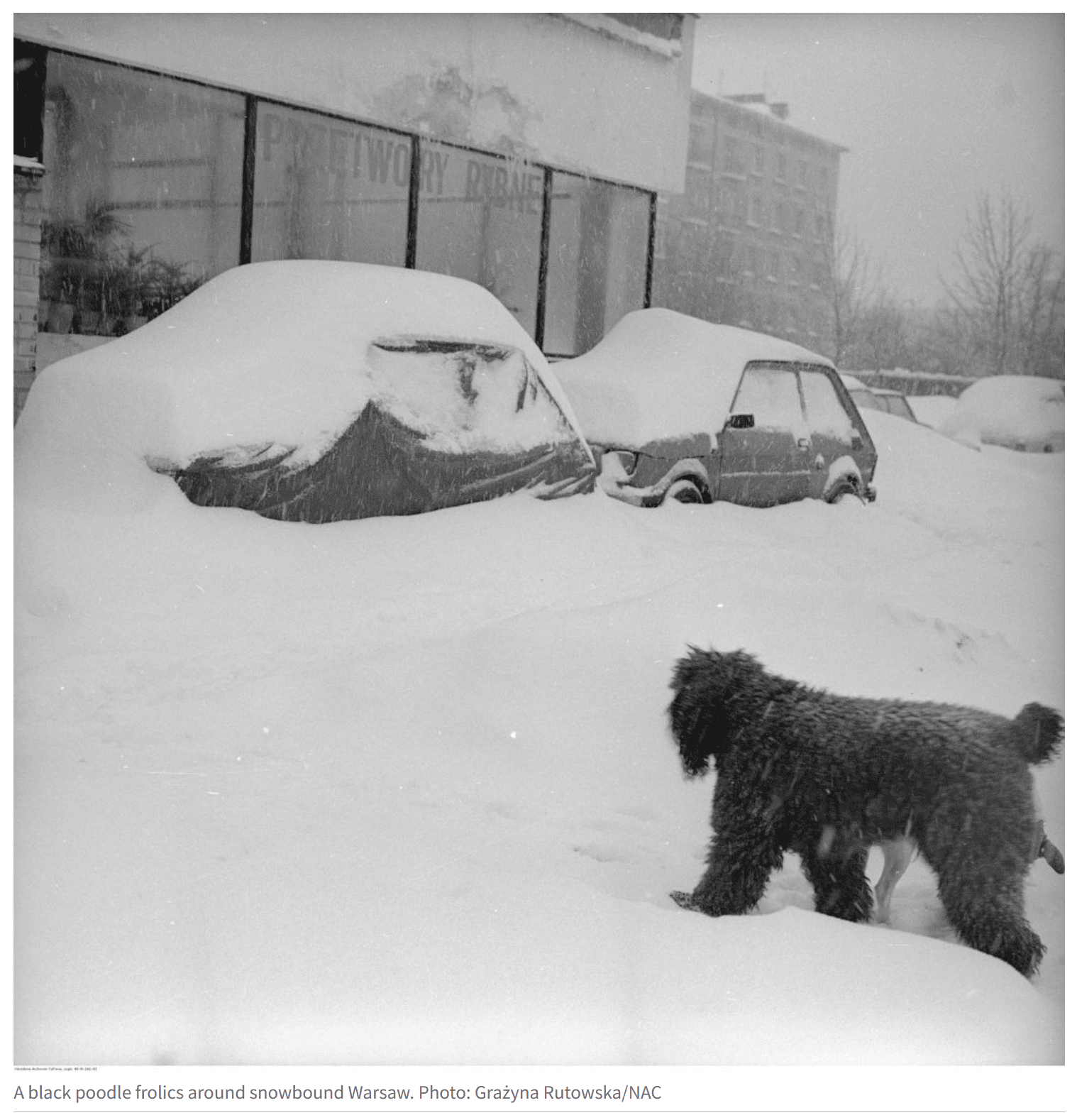

Come New Year’s Day, Suwałki found itself floundering under 84 centimeters of snow. In Łódź, 78 centimeters had fallen, and in Warsaw, 70 centimeters.

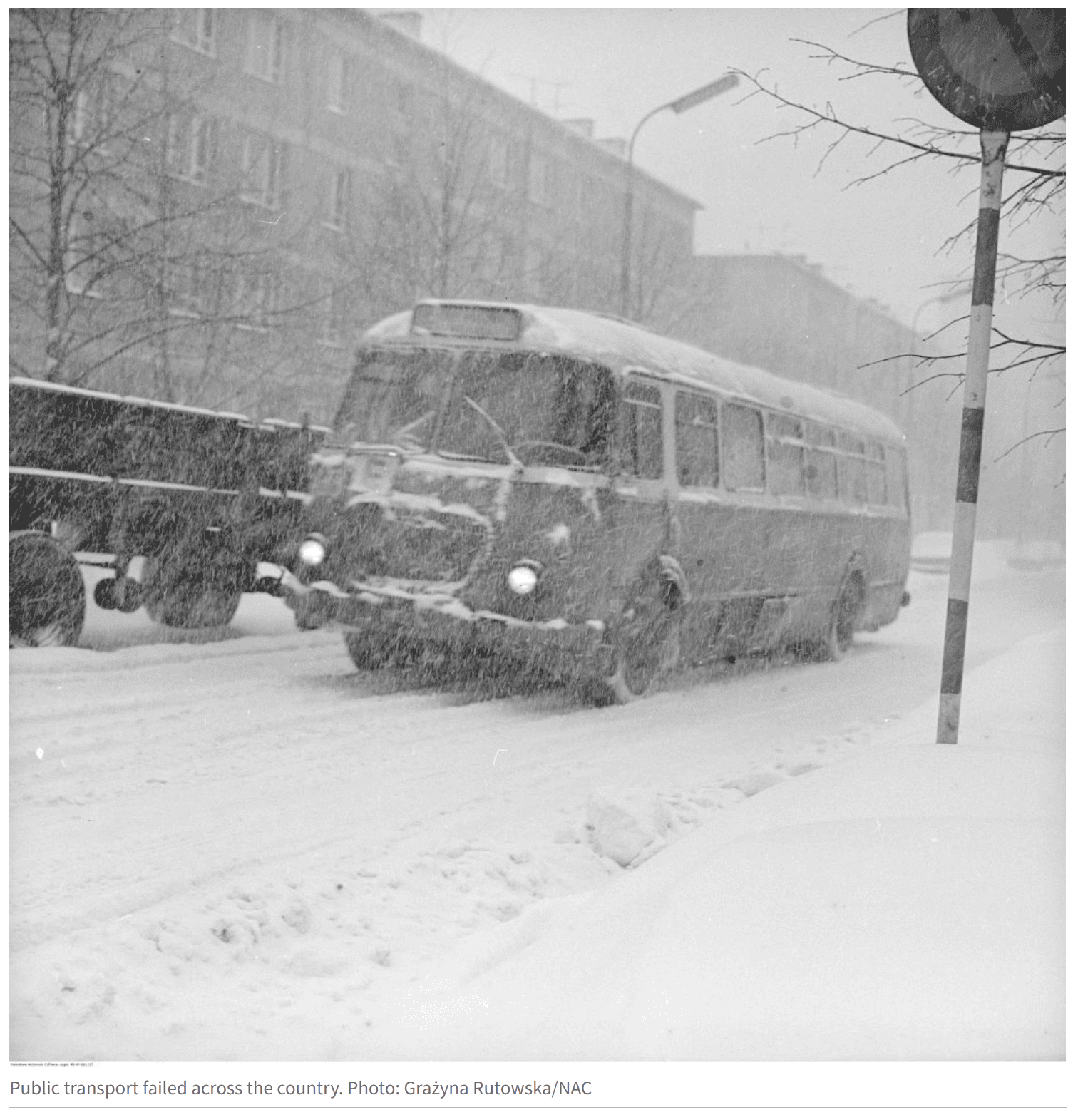

The capital proved wholly unprepared. Trams ground to a halt, and of the city’s 1,000-strong fleet of taxis, barely a dozen remained in service. The rest found themselves press-ganged into ferrying workers to heating plants. As pipes burst across the city, Warsaw shivered without heating or hot water.

PART FOUR

Next part of the article.

Listen to the next part of the article. Follow the text as you lilsten.

Further north, conditions were even more dire. In Szczecin, only a quarter of the city’s buses managed to leave their depots; other coastal towns, like Puck and Władysławowo, relied on helicopters and military transports to deliver food.

When Gdańsk declared a state of emergency, it was by no means a panic measure. Within a day, other cities followed suit, among them Poznań, Toruń, Bydgoszcz and Legnica.

Over in the port city of Gdynia, locals were met with the particularly ghostly sight of a cargo ship, the Władysław Broniewski, locked fast in ice, tilted at a rakish 35-degree angle. It would remain in this eerie, twisted pose until January 9, when crew members finally freed it after resorting to detonating small explosive charges to blast away the ice.

Rather than relenting, winter tightened its grip. With public transport paralyzed, the entire energy sector teetered on the brink of collapse. Kozienice power station, for example, had seen its daily deliveries of 80 wagons of coal slashed to just a quarter of that number.

Part five

Next part of the article follow below.

Listen to this part of the article. Follow the text as you listen.

Rails splintered and switches froze solid. Even with the army deployed to repair tracks and carve tunnel-like corridors through towering snowdrifts, other problems loomed. Deep in the coal mines, conveyor belts had seized in the cold; above ground, coal heaps lay entombed beneath ice and snow.

The ensuing power shortages left major cities shrouded in darkness. According to some reports, just boiling enough water for a single cup of tea could take half an hour.

Predictably, stores were swamped as people stocked up on whatever they could get their hands on. In a country already plagued by retail shortages, this only deepened the sense of crisis. In Olsztyn, a typical medium-sized city, over 40 stores found themselves shuttered, having nothing left to sell.

Beyond urban areas, the struggle was even more pronounced: Reszel, a pocket-sized town in the Mazuria district, was cut off entirely. In the mountains, holiday camps were turned into makeshift shelters as school groups found themselves marooned.

PART SIX

Sixth part of the article.

Listen to this part of the article. Follow the text as you listen.

Despite these challenges, Poles persevered. Warsaw resident Krzysztof Zdanowski Sr., then living in the suburb of Stegny, recalls the struggle of walking home from his parents’ apartment in Mokotów and having to hoist his child’s stroller onto a sled to make the journey back.

“Of course, mobile phones hadn’t been invented yet, and there were hardly any landlines in Stegny at the time—but no one caused a drama. You simply had to manage,” he tells TVP World.

By mid-January, the media were proclaiming victory over the elements. “The difficult battle has been won,” wrote the weekly Stolica, before heaping praise on the students, scouts and workers who had rallied together to help the army clear the roads.

But Stolica was wrong. The real battle lay ahead.

PART SEVEN

Seventh part of the article.

Listen to this part of the article. Follow the text as you listen.

Temperatures stayed bitterly low, and for the next couple of weeks bouts of sleet left the streets glazed in treacherous ice. Then, on February 2, a fresh blizzard hit Warsaw, transforming the beleaguered capital into what some newspapers described as a “subarctic landscape.”

When an appeal was issued for public help to clear the capital, it is estimated that around 600,000 people answered the call.

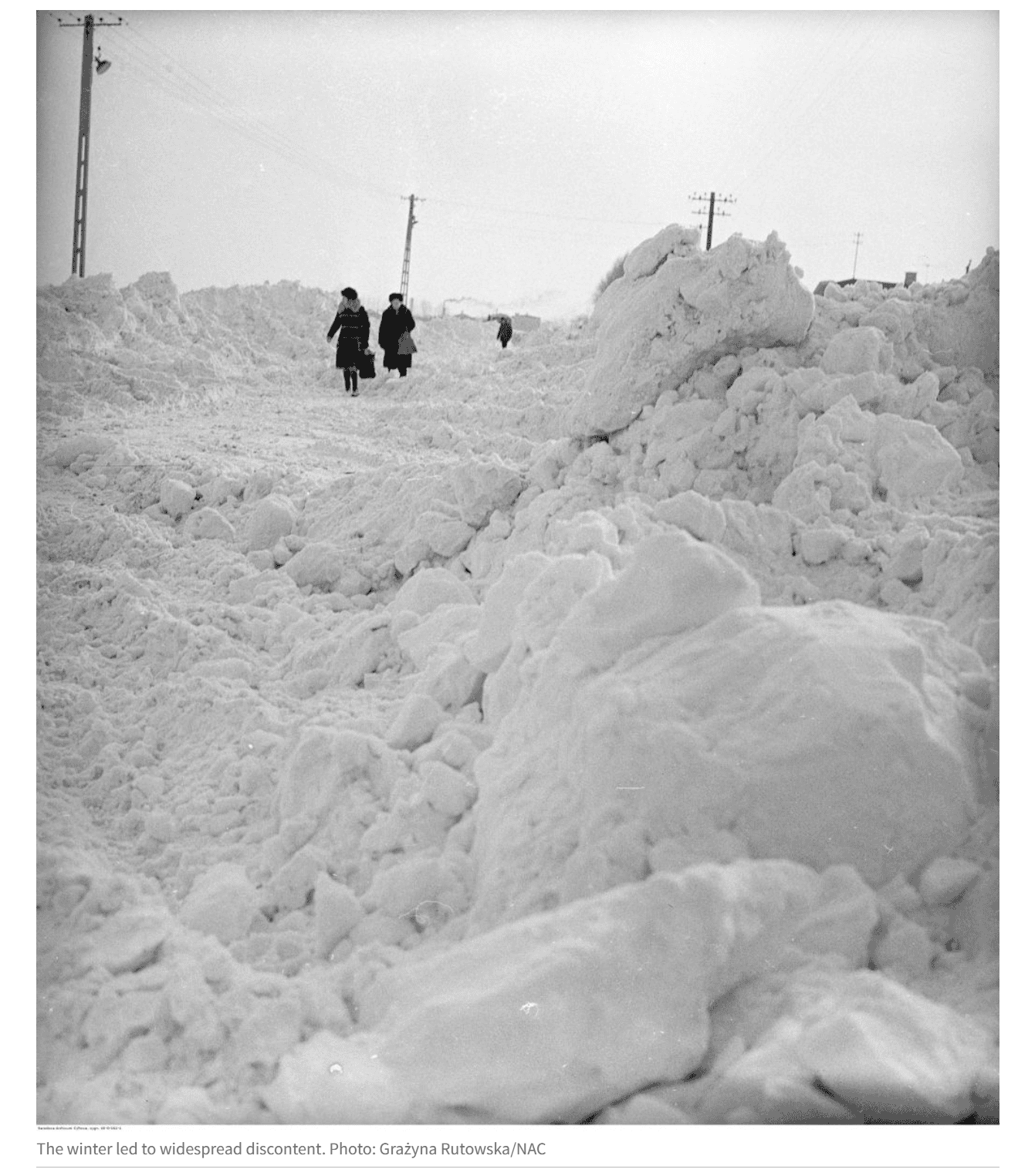

Somewhat naively, the authorities attempted to paint this response as a show of socialist unity, but the people knew better. Those who volunteered to clear the streets were furious, and many spoke openly against the system that had failed them. Discontent surged unchecked among the masses.

Once again, a burst of bad weather had left the authorities scrambling to provide for the people. In hospitals, cases of frostbite soared, with new admissions often given nothing more than a blanket and a shot of vodka. Then it got worse.

PART EIGHT

Last-but-one section of the article.

Listen to this part of the article. Follow the text as you listen.

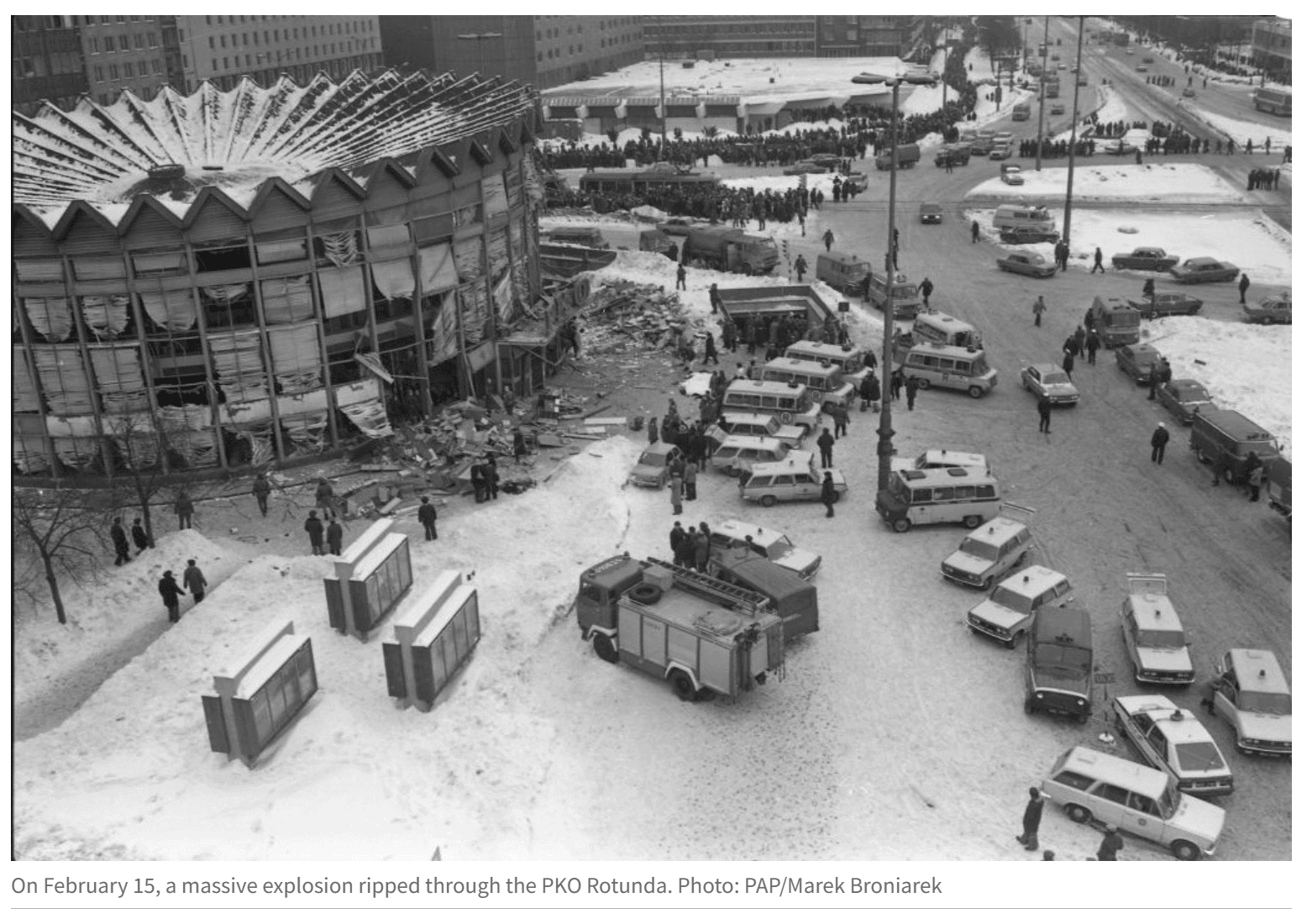

On February 15, a massive explosion ripped through the PKO Rotunda building in the very heart of Warsaw, killing 49 people and injuring scores more.

Rumors that embezzling officials had planted a bomb to cover their tracks spread like wildfire, but a subsequent investigation ruled the actual cause to be a gas explosion triggered by frost-damaged pipes and valves—the government’s inability to cope with winter had directly led to Poland’s biggest post-war disaster at the time.

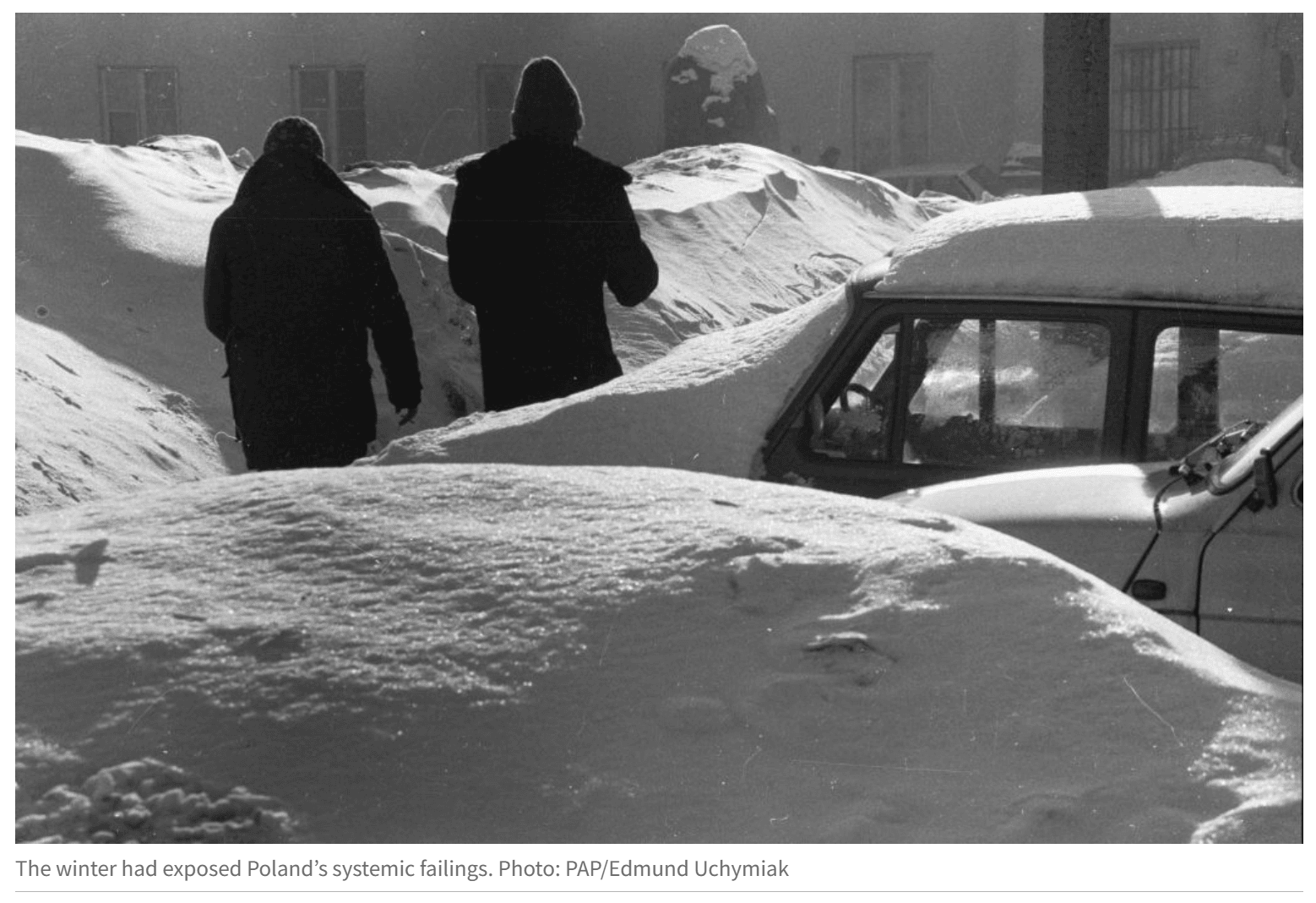

When the thaw finally arrived, Poland was a changed country. The previous year, highs had been numerous: the election of a Polish pope, the country’s first man in space and a brave run in the World Cup, but these triumphs had all simply papered over deep cracks. The winter had torn that fig leaf away, exposing Poland’s systemic failures in stark detail.

part nine

Last part of the article.

Listen to this part of the article. Follow the text as you listen.

As the snow melted, the scale of the economic wreckage became clear. Hundreds of thousands of chickens had died, vegetables had rotted and milk tankers failed to reach farms, leading to acute dairy shortages.

With factories also falling far short of their production targets, the winter had left virtually every industry sector beeping in a state of red alert. For Poland, economic catastrophe beckoned, and while the reckless fiscal policies of the 1970s had always made this a matter of time, the freeze acted as a powerful accelerator.

Another Armageddon, this time financial, was hurtling toward Poland.

part two

Discussion

Discuss the questions below.

The Winter of the Century – Poland, 1978/79

Listen to a shorter version of this story and then complete it with the missing words.

lesson glossary

Here’s a practical glossary for this lesson.

COMMENTS

Write your one version of this story. Use some of the vocabulary from this class.

0 Comments